"Be stubborn on vision, but flexible on details" - attitudes towards innovation and failure at Amazon

During a shareholder meeting in 2011, Jeff Bezos was asked a question: “If it’s still Amazon’s philosophy to make bold bets, I would expect that maybe some of them wouldn’t work out, but I am just not seeing that. So, my question is where are the losers?”

His reply is fascinating to read and gives insight into innovation at the company – specifically, his view that consistent innovation isn’t possible without acknowledging the possibility of failure. AWS was starting to really take off at the time of that quote, but it hadn’t become as massive as it is today. To put it in perspective, Microsoft Azure had just launched the year before – so even though most of us didn’t realize it at the time, the whole cloud thing was going to be a big deal.

Amazon has had a lot of successes, which I probably don’t need to mention here. With a market cap of well over $1.5 trillion as I write this, the success at least from a financial standpoint is largely indisputable.

However, can you think of the failures? The fire phone is probably the most well-known and expensive of their flops, but did you know about their travel site, built to compete with the likes of Hotels.com? How about Amazon Local, a Groupon competitor? Or Askville, a Quora and Yahoo Answers style site?

Bezos is often quoted as saying “Amazon is the best place in the world to fail”. Those failures are the end state of experiments that sometimes pay off handsomely, but which are never made in a way that risks the company. Was the fire phone worth a $200M bet? With the benefit of hindsight, it is easy to question the investment. But, when you look at the size of the smartphone market it seems clear why the risk/reward analysis pointed towards making the attempt at a company like Amazon.

So what does this acceptance of failure have to do with being “stubborn on vision, but flexible on details”? I think Bezos’ whole statement linked to above is worth reading, but let’s look at a few key parts:

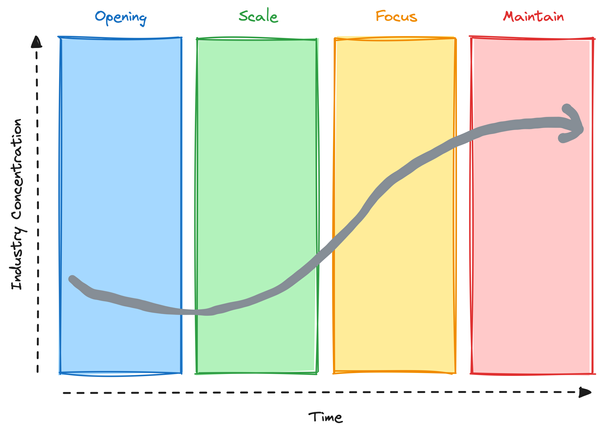

Ninety-plus percent of the innovation at Amazon is incremental and critical and much less risky. We know how to open new product categories. We know how to open new geographies. That doesn’t mean that these things are guaranteed to work, but we have a lot of expertise and a lot of knowledge. We know how to open new fulfillment centers, whether to open one, where to locate it, how big to make it. All of these things based on our operating history are things that we can analyze quantitatively rather than to have to make intuitive judgments

Amazon considers itself innovative across a lot of areas, even though the big bets are only 10% of the innovation. Much of their innovation is pushing forward on a vision that has already been proven, and the details are constantly being iterated on and perfected. They already know what they are doing, and have the data and expertise to do it even better as they go. This is an important form of innovation – and one that has a high probability of success.

When you look at something like, go back in time when we started working on Kindle almost seven years ago…. There you just have to place a bet. If you place enough of those bets, and if you place them early enough, none of them are ever betting the company. By the time you are betting the company, it means you haven’t invented for too long.

The old cliche of “if you aren’t moving forward, you are moving backward” comes to mind. Always be trying new things, make sure they are non-critical bets, and learn from either their successes or their failures.

Bezos reiterates the point of investing in probable failures, citing what has been paraphrased into the title of this blog post:

I can guarantee you that everything we do will not work. And, I am never concerned about that…. We are stubborn on vision. We are flexible on details…. We don’t give up on things easily. Our third-party seller business is an example of that. It took us three tries to get the third-party seller business to work. We didn’t give up.

So where is the separation between vision and details? Just as with any other succinct quote, there are miles of difference between hearing a single-sentence sound byte and using it to build a trillion-dollar company. Deciding that you want to “be successful” is great, but make sure that’s not the extent of your vision. If you don’t have a plan for how to “be successful”, that still needs to be part of your overall vision.

How about knowing the line between persistence, and obstinance/stupidity? Each scenario is different of course, but Bezos spends some time talking about what to do and how to handle it when you realize you are there:

But, if you get to a point where you look at it and you say look, we are continuing to invest a lot of money in this, and it’s not working and we have a bunch of other good businesses, and this is a hypothetical scenario, and we are going to give up on this. On the day you decide to give up on it, what happens? Your operating margins go up because you stopped investing in something that wasn’t working. Is that really such a bad day?

I believe that this is a key element of the culture of innovation at Amazon. They make bets, they invest time and money, and of course they expect to see success – but they are prepared to cut their losses when it is time. And they look on the bright side when it needs to happen: “Hey look, our margins are going up!”.

A big piece of the story we tell ourselves about who we are, is that we are willing to invent. We are willing to think long-term. We start with the customer and work backwards. And, very importantly, we are willing to be misunderstood for long periods of time.

Think long-term, think about your customer (make sure you are providing value!), and be prepared that your innovation won’t be an instant, overnight success. Amazon was laughed at for years and told to “mind the store” as they worked on AWS. Now, books are a very small part of their revenue – and AWS is a huge part of their profits. They were misunderstood, they persisted, and it paid off.

Even Paul Graham himself, whose incubator has likely provided the seed round on more billion-dollar companies than anyone else, says “Now I don’t laugh at ideas anymore, because I realized how terrible I was at knowing if they were good or not.”

Here are my takeaways:

- Continually innovate in areas where you know the vision works, where you are iterating on details rather than the big picture.

- Spend some of your effort on “big bets”, which may or may not pay off.

- Be persistent with your vision, but don’t let any “big bets” kill your company.

- When it is time to cut your losses on a bet, do so.

- Be prepared to work at your vision for a while. Recognize how many ideas are an “overnight success years in the making”.

There’s no book that will tell you how much of your time and effort should go towards the “big bets” at your company. There is no blog post that will explain in perfect clarity where the line is between vision and details in your particular circumstance. There is no training course to tell you how long you should work with an idea, and when to cut your losses.

Regularly and consistently thinking about these ideas will give you perspective to better make those decisions though. You won’t make the right decision all the time, but an intentional approach that respects these principles will greatly increase your odds of success.

In the end, isn’t that all we can really hope for?